- English

- DEUTSCH

- SPANISH

- FRENCH

Professor Zey Suka-Bill is a nationally recognised leader in creative and inclusive education, with over 25 years of experience shaping teaching, research, and institutional culture across the UK higher education sector.

As Pro Vice-Chancellor for Education and Student Success at the Royal College of Art, Zey leads on advancing educational excellence, fostering interdisciplinary learning environments, and ensuring that students are supported to thrive academically, artistically and professionally.

Her leadership is rooted in equity, co-creation and student agency, with a strong focus on closing awarding gaps and improving outcomes for underrepresented groups in creative disciplines. She has contributed to sector-leading research on immersive technologies, curriculum equity and creative apprenticeship policy.

Before joining the RCA, Zey served as Dean of Screen at the London College of Communication, University of the Arts London, where she led one of the UK’s largest clusters of programmes in film, television, animation and immersive media. She also held the role of Interim Pro Vice-Chancellor at UAL, with cross-institutional responsibility for student experience, digital learning, academic registry and wellbeing.

I grew up in a West African family. My parents were first-generation immigrants to the UK. My dad came over on a scholarship in the early 1960s, and my mum followed in the 1970s. We grew up very aware of that journey and what it meant.

My parents were always vocal about why they came to the UK. They said that if they hadn’t had children, they would have stayed where they were. Their move was about creating access and opportunity for us through education. We grew up knowing that there was an expectation for us to make a mark in the world, and that they had sacrificed for us to do so. Even though they never spoke of it as a sacrifice, they always described it as a joy to give us the chances they didn’t have.

That sense of service and purpose, of being useful and contributing wherever you are, has always been part of my story. In our household it was not really an option to be ineffective or to keep your talents to yourself. You were expected to use them to help others and make a difference. So I think that is where my leadership journey began, in that family narrative of responsibility, service and impact.

I have been fortunate to build a career that connects creativity, teaching and leadership. I worked in industry as a photographer, researcher and exhibiting artist, and later returned to higher education to teach. From there I have had the privilege of holding different leadership roles in higher education, and that journey has brought me to where I am today.

I have been fortunate to build a career that connects creativity, teaching and leadership.

That sense of service has always guided me, even when I was not working in what my family might have considered an “approved” profession. I studied at Central Saint Martins and at what was then the Polytechnic of Central London. When I went into arts education, there were very few people who looked like me teaching, and even fewer in industry. I cannot recall seeing anyone from a global or working-class background in those spaces.

So, when I decided to return to education, I knew I would probably be one of only a few Black women that students would encounter in their academic journey. I was very conscious of that and understood the responsibility that came with it. I knew that I wanted to show up as a role model, not in a performative sense, but because I understood how powerful it would have been for me to have had someone to look up to when I was a student.

From the very beginning, my motivation was to make change happen in the spaces I entered. I wanted to improve equity and inclusion within the institutions where I worked. Over the years, I have led initiatives to reduce attainment gaps that are ethnically or socially constructed, where one group of students consistently performs better than another. I have worked hard to make transitions smoother for students from underrepresented backgrounds.

When I joined the University of the Arts London about eleven years ago, there was an assumption that students from certain backgrounds needed to do more to “catch up”. They were expected to attend pre-sessional programmes or extra sessions to help them develop a sense of belonging. One of the things I am proudest of is that we changed that mindset. We began to ask how the institution could meet its students, rather than expecting students to meet the institution.

My work has always been about accessibility, but I also believe access is not enough. It must be matched by real opportunity and genuine progression. It is one thing to open the door, but quite another to ensure that people feel they belong once they are inside.

A large part of my work has also focused on what the sector refers to as decolonisation. For me, it is about having brave, courageous conversations about the ways in which we teach and ensuring that those approaches are inclusive for everyone. It is not about loss or removal from the curriculum, but about enrichment and context. It is about asking how everyone can see themselves reflected in what we teach and in the knowledge we share.

That has been the thread running through much of my work – building belonging, widening access, and reimagining how higher education can truly serve every student.

We began to ask how the institution could meet its students, rather than expecting students to meet the institution.

I often think back to my doctoral research. It revealed that across the education sector there was a real appetite for things to change and for equity to be taken seriously. Yet the systems themselves did not make it easy. There is still a concentration of power that prioritises reputation and preservation, which can make dismantling inequitable structures incredibly difficult.

For me, genuine inclusion requires a redistribution of power. I celebrate initiatives such as Black History Month, but they cannot be symbolic. At their core, they must shift how power operates. That redistribution should shape student outcomes, career progression, curriculum design and recognition across institutions. Otherwise, it risks becoming a symbolic exercise that leaves existing hierarchies untouched.

The deepest tension, I think, lies in the space between change and comfort. Change is uncomfortable. Many of us have inherited systems that protect and serve some people more than others, and the question becomes whether we are willing to confront the discomfort that comes with losing privilege, certainty or influence.

When we talk about equity, we are talking about power, and that means asking difficult questions: What might I lose? What will change about my standing or recognition in this institution? Those are emotional questions as much as structural ones. We need to hold and confront those anxieties honestly if we are serious about building systems that are fair and inclusive.

For me, genuine inclusion requires a redistribution of power. I celebrate initiatives such as Black History Month, but they cannot be symbolic. At their core, they must shift how power operates.

Real inclusion cannot be performative. It has to be embedded in culture, policy and accountability. It requires structural change and a willingness to face the emotional labour that comes with that change. When institutions focus on the symbolic, it can create comfort without transformation.

To move beyond that, leaders need to look critically at how decisions are made, who has a seat at the table and what redistribution of power truly looks like. The work of equity should be as much about systems as it is about relationships, values and the courage to sit with discomfort until something real shifts.

When institutions focus on the symbolic, it can create comfort without transformation.

That is such an important question. The double bind of representation is beginning to be spoken about more openly, and it is something I deeply relate to. Visibility can be empowering, but it can also be exhausting. You become, whether you like it or not, a symbol of progress, while still navigating systems that were never designed for you. There is an expectation to lead, to fix, to explain, to embody diversity – all at once.

For me, what has made the difference is the people around me. I have been fortunate to work with colleagues who genuinely believe that change should not rely on individuals alone. They practise collective accountability and share the responsibility for equity work. Throughout my career, I have had advocates who have spoken my name in rooms I was not in, not only as a “diverse” voice but as a contributor to the core mission of education and student success.

Having those allies – people who see you fully, who listen, who give you credit, who make space for you to try and fail – has been transformative. It has reminded me that the work of inclusion is not mine alone to carry. Real progress happens when responsibility is shared, and when those with power use it to open doors for others.

Real progress happens when responsibility is shared, and when those with power use it to open doors for others.

The first thing I would say is to be yourself. Early in my career, I had people tell me that I would need to change how I spoke or how I behaved if I wanted to progress. I have never seen myself as a traditional leader. Yes, I hold a senior position, but I often say, “I am not that kind of Pro Vice-Chancellor, and I am not that kind of Professor.” I am very much myself.

So my first piece of advice is to know that you belong. Your presence and your values have a place wherever you are. Be your whole self, but also protect yourself. Institutions have different capacities to change, and not every environment is equally safe for authenticity. Sometimes, being fully yourself can lead to harm rather than good, and it is important to be discerning about that.

Ultimately, I would encourage emerging leaders to come into their spaces with confidence and conviction. Leadership can carry a heavy weight of expectation, but it also offers an opportunity to redefine what leadership looks like. Stay rooted in your values, build a community of support and remember that authenticity is not a liability. It is your greatest strength.

You just have to find the right place for it to flourish. That may take time, and perhaps a few changes along the way, but you will get there.

Your presence and your values have a place wherever you are.

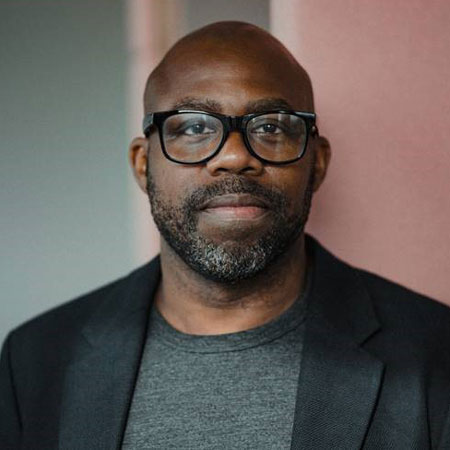

Professor David Mba is Vice-Chancellor of Birmingham City University and a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering. A distinguished academic and leader in higher education, he has held senior roles at several UK universities, including the University of the Arts London, De Montfort University, London South Bank University, and Cranfield University.

David’s leadership is guided by a commitment to equity, authenticity and excellence. He has led institutional strategies to close attainment gaps, expand access and embed inclusion across teaching, research and governance.

An engineer by training, he studied Aerospace Engineering and earned a PhD in Mechanical Engineering from Cranfield University, where he received the Lord King Norton Gold Medal for the most outstanding doctoral thesis.

Beyond academia, David chairs the Birmingham Cultural Compact, co-chairs the Black Leaders in HE Network, and serves on the Board of Advance HE. He is a Principal Fellow of the Higher Education Academy and a leading voice for inclusive, values-driven leadership in higher education.

I began my academic career at Cranfield University, where I completed a PhD in Mechanical Engineering and received the Lord King Norton Gold Medal for the most outstanding doctoral thesis. That recognition gave the university the confidence to appoint me as a Research Fellow, and later I progressed into lecturing and senior academic roles.

Leadership was not something I had planned. I was very content in technical work and loved being hands-on with machinery and research. But at one point, our school went through a change in leadership, and I found the new direction uninspiring. It felt like business as usual. I remember thinking, I could do more, I have ideas.

That moment was a turning point for me. I began to explore what leadership could look like and soon started applying for Dean roles outside Cranfield. That step marked the beginning of my leadership journey and my transition from technical work to shaping institutions and people.

Leadership was not something I had planned.

My leadership is grounded in three values: equity, authenticity, and liberty.

Equity is fundamental. If something is not fair, it bothers me deeply. Whether I am making decisions about staff or students, I always ask whether my decisions are fair to everyone and whether I am truly reflecting the diversity people bring. I am mindful of those differences, but fairness must be consistent. I like to sleep well at night, and that means leading in a way that allows my conscience to rest easy.

These values are especially important at Birmingham City University, where most of our students are from minority ethnic backgrounds. Yet, like many institutions, we still see disparities in outcomes. That is something we are absolutely not prepared to accept. I am privileged to be in a position to tackle these issues head-on and to put real action behind the words. It is not enough to state intentions. We must deliver measurable change.

I am mindful of those differences, but fairness must be consistent.

There are two ways to look at this. Personally, my identity has not changed how I lead, because my values remain constant. In fact, when leadership feels lonely, I hold on to those values even more tightly.

Practically, my identity has shaped how I show up. It is important that I lead by example. At BCU, I have worked to ensure that my executive team reflects the student body, so that students can look up and see themselves represented. Representation matters, especially in a sector that still struggles with institutional racism.

This commitment extends to how we recruit and appoint people, from who sits on interview panels to how we make decisions. These processes are not new, but they must be lived out in practice, not just stated. Leadership is temporary. We are all caretakers. During my time, I want to inspire others, create space for everyone to thrive, and help build the next generation of leaders from diverse backgrounds.

Leadership is temporary. We are all caretakers.

The biggest tension lies between talk and action. For decades, higher education has been gathering data, running surveys, and making statements about racial inequity, but very little has changed. The conversations have gone on too long without clear evidence of progress.

For me, the test of seriousness is in the outcomes. Are ethnicity pay gaps closing? Are senior leadership teams representative of the communities they serve? Are student attainment gaps narrowing? Until we can answer yes to these questions, the work is unfinished.

I have been vocal about the need for mandatory reporting of ethnicity pay gaps, in the same way we do for gender. When the government consulted on this, I called for universities to take a unified stand. Some institutions report openly, others hide the data deep on their websites. Imagine the signal we could send if, as a sector that has been called institutionally racist, we collectively agreed to report and act on that data.

At BCU we are tackling this directly. My goal is to bring our pay gaps to the point of statistical insignificance, so that everyone, regardless of ethnicity, gender, or background, knows they will be treated fairly and rewarded equitably.

The conversations have gone on too long without clear evidence of progress.

Symbolic gestures are not enough. Real inclusion is about evidence of change. We need to move away from statements and towards results.

That means embedding equity into institutional accountability. It means transparent data, fair promotion pathways, and leadership teams that reflect the diversity of our students. Until universities show clear, measurable progress, people will not believe that the commitment is genuine. Inclusion must be lived, not performed.

Inclusion must be lived, not performed.

Resilience for me comes from purpose. My purpose is to serve students. When faced with difficult decisions, I ask myself what is best for them. When you view leadership through that lens, the path becomes clear.

My network also keeps me grounded. Having people around you who remind you of your journey and your achievements is essential.

There is also a balance to maintain as a Black leader. It can be challenging to navigate the line between advocating strongly for equity and leading inclusively for everyone. It is a constant calibration. But I would rather face that tension than stay silent. Authenticity keeps me grounded.

Resilience for me comes from purpose.

First, be authentic. Do not try to lead like someone else. When you lead authentically, clarity and direction follow naturally.

Second, strive for excellence. Doors do not always open easily for us, so be exceptional at what you do. Excellence creates credibility and opportunity.

Third, build your network. Surround yourself with people who challenge, support, and remind you of your value. Networks are not just professional; they are personal sources of strength and encouragement.

Finally, be visible. Do not shy away from taking space or speaking up. If you are authentic, you cannot go wrong.

Jeanette Bain-Burnett is Executive Director for Policy and Integrity at Sport England, where she leads work to ensure integrity and inclusion are central to the nation’s sport and physical activity system. Her remit spans thought leadership on key policy issues, supporting a sector that enables everyone to access the benefits of movement and participation.

Before joining Sport England in 2022, Jeanette served as Director of Participation at the Trussell Trust, where she shaped strategies for community engagement and inclusion. She previously held senior roles at the Greater London Authority, including Assistant Director for Communities and Social Policy and Head of Community Engagement.

Jeanette’s career began in the arts and cultural sector as Director of the Association of Dance of the African Diaspora and later as a strategic consultant for organisations such as Arts Council England, Creative Lives and BBC Arts.

I grew up in Jamaica where there was always something to do. I did a lot of sport, but the thing that moved me was dance. From about seven years old, school dance classes lit something in me. As a teenager I joined a community dance company. It was faith based and it became a creative home. The director saw leadership potential in me and gave me small chances to lead. That was my first experience of being shaped by a community leader with a clear vision.

I moved to the UK to continue with dance and the performing arts. I performed, did postgraduate study in choreography at Middlesex, and then realised I wanted to enable others. I could have worked to become a choreographer, but I felt my strengths were in building organisations and creating the conditions for others to succeed.

I applied for administration and project roles and kept seeing an exhibition poster, Black Dance in Britain. I applied to the organisation behind it. They called and asked whether I had noticed they were actually recruiting a Director. I had the experience, but I had not organised my story to see it. I became the first Director of ADAD, the Association of Dance of the African Diaspora. It was a small organisation and that role made me. I defined what leadership looked like there, learned by doing, and led a network and movement focused on moving artists from the margins to the mainstream.

Later I freelanced, then joined the Greater London Authority to lead community engagement at City Hall. Under the Mayor, nothing reached his desk if it had not addressed community need, which made the work both political and deeply practical. Post-COVID I moved to Bristol for family balance and joined the Trussell Trust to lead participation strategy. It was short, but I learned a great deal about structural change in the anti-poverty space and how institutions work with communities at the right pace. I am now at Sport England, leading policy and integrity so that inclusion, access and fairness are central to how people experience sport and movement across the country.

I learned a great deal about structural change in the anti-poverty space and how institutions work with communities at the right pace.

That’s such an interesting question. I actually did a women’s leadership course earlier this year, and we spoke a lot about barriers that women face in leadership. Some of those experiences resonated with me, and others didn’t.

I grew up in Jamaica with quite a privileged and secure background. My parents were professionals, and I didn’t carry the burden of representation. I didn’t have to justify my existence or prove that I belonged. So when I moved to the UK, it was a kind of cognitive dissonance – people often expected that I would have low confidence or need extra help because I was a Black woman. And my reaction was, yes, I may need support, but that’s because I’m human, not because I’m Black.

That experience made me more reflective about how barriers show up. Some are structural – around access to safety, security and support. Others are institutional – based on perceptions and stereotypes. And all of them sit on a very long legacy of systemic discrimination that still shapes how people are treated.

One of my early experiences at City Hall captured this perfectly. I got into the lift and pressed number eight for the Mayor’s floor. A woman looked at me and asked if I was one of the secretaries. I said, “No, I’m the new Head of Community Engagement.” You could see the colour drain from her face. It was such a small moment, but it revealed so much about bias, and it made me determined to lead differently.

I don’t ever want to reproduce those same patterns. Inclusive leadership isn’t automatic just because you’re a Black leader. It’s a practice, one that involves humanising other people’s experiences and asking real questions about their stories, rather than relying on the stereotypes we all carry.

People often expected that I would have low confidence or need extra help because I was a Black woman.

Across every sector I’ve worked in – arts, policy, community and sport – there’s a genuine appetite for equity. But there are also structural realities that make it hard. Power is concentrated in certain places. Organisations worry about what change means reputationally, or they hold on to comfort.

I always say it’s not enough to celebrate diversity or mark moments like Black History Month. These things are valuable, but only if they’re backed by a redistribution of power that shapes who gets opportunities, who is recognised and whose voices are heard.

One of the hardest truths is that real inclusion demands emotional work. It means leaders confronting their own fears of loss – loss of certainty, influence, privilege. That anxiety sits deep in institutions. Until we’re able to name it, hold it and move through it, we’ll keep circling around the same issues.

One of the hardest truths is that real inclusion demands emotional work.

I’ve learned that taking on that burden isn’t good for anyone. It’s not good for me, and it’s not good for the people I want to help.

These days, when I’m asked to carry too much of that responsibility, I often turn the question around and ask, “Why is that my responsibility alone?” I will always choose to lead on inclusion and mentorship because it matters to me, but it has to be shared. The next frontier of inclusion is when everyone owns the agenda – not just those most affected by inequity.

I sponsor our culturally diverse staff network, I coach and mentor, and I try to model what shared ownership looks like. But I also draw boundaries when it becomes exploitative of my energy. Sometimes I simply rest. Rest is part of leadership too.

Sometimes I simply rest. Rest is part of leadership too.

First, be clear about your message, what you stand for right now, and hold it. It will evolve over time, but it’s important to know what drives you and not to compromise it.

Second, prioritise wellbeing. That means emotional, physical and financial wellbeing. There’s often a false choice between doing work you love that doesn’t pay or doing well-paid work that drains you. Find the balance. Sustainability is part of leadership.

And finally, stay connected. Build spaces of belonging and joy. Leadership carries expectation, but it’s also a chance to redefine what leadership looks like – to root it in humanity, purpose and care.

It’s important to know what drives you and not to compromise it.

Shane Ryan is Senior Advisor to The National Lottery Community Fund and the former Global Executive Director of the Avast Foundation. He previously served as Deputy Director at The National Lottery Community Fund and was Chief Executive of Working with Men (now Future Men), where he led the organisation to national recognition for its evidence-based work on conflict resolution, fatherhood, masculinity and youth development.

With more than twenty-five years’ experience working with young people and communities, Shane has held senior roles across the voluntary and public sectors, including managing the UK’s first mobile healthcare facilities for the NHS and serving on a Home Office secondment. His work has taken him across the UK, the USA and Japan, shaping policy and practice in youth engagement, equity and inclusion.

A frequent advisor and public speaker, Shane continues to champion community-led solutions and inclusive leadership across civil society.

I did not really have a chosen career path. I have always been more of a quest person. I have always worked where I have had a burning desire to change something, to work with others and to make a difference.

Where I am now is the result of choices made at different times based on what mattered most to me in that moment. I have always asked myself where I could be useful, where I could be helpful to my community, and where I could create connection between people. Sometimes that has been because I had the social or community capital to move things forward, and sometimes because other people believed I did.

Several experiences have shaped who I am. My time in care as a young person was one of the first. It influenced my understanding of systems, power and fairness. Long before I began working in the voluntary sector, I volunteered in it for about ten years. That pro-social drive has always been part of me.

I have always wanted to create platforms for others to have a voice rather than seeking one for myself. I worked in children’s homes, in the homelessness sector with St Mungo’s, and on housing estates with people struggling with addiction. Later, I worked with young fathers, many of them teenagers.

I remember one young father in Greenwich who was fifteen. He was doing an extraordinary job as a parent, but there was simply no system designed for him. There were mother and baby hostels but nothing for fathers. It showed me how rights and opportunities that are written in law can vanish in practice when systems fail to recognise you.

Those moments taught me to focus on inclusion, fairness and humanity – not in abstract terms, but in the details of people’s lives. My career since then, including my time at Future Men, has been about ensuring that those who are often excluded can access real opportunity.

Those moments taught me to focus on inclusion, fairness and humanity – not in abstract terms, but in the details of people’s lives.

Throughout my career, attitudes toward race have shifted, but often it feels like one step forward and two steps back. Many of the freedoms and progress we fought for thirty years ago are being fought for again today.

In my early years, I focused on being a good leader first rather than a Black leader. Over time, I realised those two things cannot be separated. Many of my experiences were shaped by race. Ignoring that meant I could not properly support others navigating similar spaces.

Leading as a Black man in the voluntary sector is complex. Sometimes the very institutions that see themselves as progressive can still limit or silence the communities they claim to serve. That makes the work harder because you find yourself negotiating not only external resistance but also the contradictions within the sector itself.

When you are often the only person of colour in the room, everything you say carries a different weight. The higher you go, the more that isolation can grow. It takes confidence and self-belief to keep contributing meaningfully in those spaces.

Race has undoubtedly shaped my trajectory and opportunities. But I have also learned that being right is not enough. In this work, you can have justice on your side and still make no progress. What matters is building movements, changing minds and creating the conditions for lasting change.

What matters is building movements, changing minds and creating the conditions for lasting change.

The biggest challenge is that real inclusion takes time, intention and effort. Many people underestimate how much work it takes to bring communities together and to ensure equity in practice. It is easier to design for people than to design with people.

Working in a way that genuinely shares power is messy, slow and demanding. But that is also where the transformation happens. True inclusion cannot be reduced to consultation or tokenism. It means redistributing power, inviting new voices to shape outcomes, and being willing to sit in the discomfort of that process.

Real inclusion takes time, intention and effort.

Symbolic gestures are easy. Genuine inclusion requires understanding, value and intention. I remember challenging my son’s school one Black History Month when they focused on Thierry Henry. There is nothing wrong with footballers, but it showed how shallow the approach can be when institutions only know how to celebrate visibility rather than substance.

When people truly understand the value that Black people bring to every sphere of life, inclusion moves from tokenism to truth. Black History Month should not be an add-on. It should be a reminder of how deeply our stories, work and brilliance are woven into this country’s fabric.

Our involvement in British life is not ornamental. It is foundational. From the industrial revolution to the present day, our contribution has been immense, yet often untaught and unacknowledged. Inclusion is not a moral favour. It is about recognising excellence, equity and value – for everyone.

Our involvement in British life is not ornamental. It is foundational.

The fewer people who look like you in a space, the more microaggressions you experience. They erode confidence and energy. Being the most senior Black person in an organisation often means carrying additional, invisible labour. Colleagues come to you with their struggles because they trust you to understand. That is not in your job description, but you take it on because it matters.

It can be heavy. I rely on family and friends to ground me. They are why I can cope even when things feel overwhelming. Their support allows me to keep giving to others.

It is also important to recognise the limits of what we can change within systems. Sometimes those of us working inside them end up reproducing the same patterns we set out to dismantle. That is why reflection and community matter so much.

Family, friendship and solidarity with other leaders keep me steady. They remind me why I do this work and what it means to show up with integrity.

It is also important to recognise the limits of what we can change within systems.

Be true to what you believe in. That belief will keep you going when nothing else does.

Build and nurture your networks. They open doors, provide support and create opportunities you might not even see yet. Get a mentor. Mentorship is powerful. It accelerates learning, offers perspective and keeps you accountable.

And above all, do work that inspires you. Life is too short to be committed to things that do not move you. I am near the end of my career and it has gone quickly. But I can look back and feel that I have used my time well. I have worked on things that mattered, that carried conviction, and that moved people and systems forward. That is all you can ask for.

Ebele Okobi is a global leader recognised for her work at the intersection of technology, human rights and social impact. She has held senior roles across the private and nonprofit sectors, including leading Public Policy for Africa, the Middle East and Turkey at Facebook, and establishing the first human rights department at Yahoo – the first of its kind in the technology industry.

Her career has been defined by a commitment to equity, dignity and justice, and by building teams and cultures that centre inclusion and social purpose. She has also worked in the nonprofit sector advancing women in business and in the arts and culture space supporting creators who use art to speak truth to power.

Ebele currently serves on the Board of the Museum of West African Art (MOWAA). She has previously served on the Boards of a range of organisations including the British Council, the Young Vic, Whitechapel Gallery, Chisenhale Gallery, Williamstown Theatre Festival and CARE International UK.

Today, she continues to advise mission-driven organisations and initiatives that seek to create spaces of joy, safety and radical imagination.

A big part of who I am comes from being Nigerian. Both my parents are Nigerian. We are Igbo. I grew up with a strong sense that many people had sacrificed for me to be where I am. I always felt I was standing on the shoulders of giants.

At the same time, I had a strong sense that I could do anything. There is a Nigerian saying that if you come home with 98 percent, your parents will ask who got 99 percent, and then they will say, “Does that person have two heads.” My parents never said that to me, but the message was there. You can do anything.

Those two things together shaped who I became. I became a lawyer because, as the daughter of immigrants, there were four choices. You could be a doctor. You could be a lawyer. You could be an engineer. Or you could be a disgrace to your family. I thought I would be a doctor until I shadowed one at my mother’s hospital when I was eleven. I came home and decided that was not for me. I loved to read, so I decided to be a lawyer.

In the 1990s, after law school, the path was clear. You went to a prestigious firm. Within two years I realised I hated it. I did not respect the lives of the people I was meant to look up to. So I walked away. That decision to leave something I was meant to want has shaped my life.

I took a year off to travel and volunteer in the nonprofit sector. When I came back to New York, it was two weeks before September 11. That experience was a real turning point for me. It made me reflect deeply on what matters most and led me to decide that I would only ever do work that was aligned with mission and purpose.

I always felt I was standing on the shoulders of giants.

After that I worked in the nonprofit sector for four years. I realised that what mattered most to me was impact. I wanted to see change happen. I started to wonder if I could bring that same mission-driven mindset inside companies rather than standing outside.

I went to business school in France to learn French because I wanted to work across Africa. I was recruited to Nike and it was there that I saw how Western companies operated in Africa and how important it was to have Africans shaping those decisions.

Later I joined Yahoo to build their first ever human rights department. It was the first at any tech company. It was about understanding how technology and human rights intersect and making sure governments did not misuse digital platforms.

After seven years, I left. Around that time, I had twin children. When I had a Black son, I knew I could not raise him in America. The violence against Black boys was too much. I took a role at Facebook leading public policy for Africa and moved my family to London.

At Facebook I wanted to do policy differently. Not to walk into countries and tell them what legal frameworks should look like, but to engage honestly and collectively with the people affected. I built a diverse team across Africa, the Middle East and Turkey, hiring brilliant people who had often been overlooked. That was one of the great joys of my life.

Over time the environment became harder. I was trying to create safe spaces for others without having one myself. I left Facebook in 2021 and since then I have been focused on creating spaces of joy, safety and radical imagination. I have supported artists and activists who use culture to speak truth to power.

I also spent time exploring venture capital and briefly worked at OpenAI, but I realised that the values of big technology companies are now completely misaligned with mine. I am now thinking deeply about what freedom means, how to live it, and how to model it for others.

I wanted to do policy differently…to engage honestly and collectively with the people affected.

My identity as a Black woman has influenced everything about how I lead. At Facebook I knew what it was like to be a Black woman, and an outspoken one, in spaces that were not built for me. I wanted to create an environment where people could be their full selves.

Leadership for me is about recognising privilege and using it to create opportunities for others. I knew that because of my education and background, I had access that many brilliant people from across the continent did not. I wanted to open those doors. I wanted to build a team that reflected the richness and diversity of the people we served.

I wanted to create an environment where people could be their full selves.

Power and equity are even starker now than they were a few years ago. Equity is about sharing power. It should not be that there are systems that privilege some people and harm others.

Nothing has made that clearer than what we are witnessing in Palestine. Watching how power justifies itself and corrupts has made it even more urgent to dismantle systems of harm. The challenge is holding the line. Refusing to normalise what should never be acceptable, even when powerful forces want you to.

Most of what we see around Black History Month is performative. Organisations that do nothing to change inequity for the rest of the year suddenly remember Black people in October. Real inclusion requires people with unearned power to step aside. Most do not want to.

For those of us who are often used as tokens, there is power in refusal. We can refuse to legitimise gestures that are hollow. There is something about this moment that feels different because people are saying with their full chest what they truly believe. Many are open about wanting to maintain inequity. It is painful but also clarifying. At least now we know what we are fighting.

We can refuse to legitimise gestures that are hollow.

One thing that grounds me is knowing that the work matters even if I never see the outcome. Every liberation movement teaches us that the work is necessary even if you do not see the promised land. That perspective protects me from despair.

The second thing is solidarity. Nothing meaningful has ever been achieved alone. Change comes through genuine solidarity, not social media gestures but real, shared struggle.

The third is joy. Joy is essential. Communities that have endured oppression have always carried joy. Music, humour and laughter have sustained us. I often ask people, half joking and half serious, “How are you finding joy in the middle of the fall of empire.”

The last is history. When resistance is fierce, you can start to doubt yourself. But if you look at people like Ida B Wells or Malcolm X, the level of opposition they faced showed how right they were. Systems of harm ignore what does not threaten them. The more they push back, the more impact you are probably making.

Community, love and laughter are what have always rescued us.

Joy is essential.

Nobody does it alone. The Western model of leadership loves the story of the single hero, but everything meaningful has always come from community.

Especially in the United Kingdom, solidarity among Black people needs to deepen. Even if you are not leading movements, connect with others. There is no such thing as being the special Black person. You are not invisible because you distance yourself.

We are connected to every struggle for justice. No one is coming to save us. We are who we have been waiting for.

As the Head of Commercial Strategy and Portfolio at The Francis Crick Institute, Basma Jeelani is shaping a new role at the Institute, expanding the translational and commercial offering from The Crick. We spoke with Basma about her experience working in the science and research sector.

… Basma explained. “There are many changes happening around us including regulatory and policy shifts, evolution of public-private partnerships, development of ecosystems, continued growth of startup and spinout activity, expansion of research expertise and infrastructure. All of these provide opportunities for organisations like The Crick to diversify approaches to financial sustainability, external engagement, and future reinvestment into research and innovation”.

Contrary to common perceptions of STEM fields, Basma has experienced strong female representation throughout her career. “I have been fortunate to have inspiring female role models both in my family and throughout my professional journey. Learning from them and observing how they navigate challenges such as career advancement, work-life balance, and especially leadership development has been crucial for my growth”.

Flexibility stands at the centre of Basma’s workplace philosophy, which she sees as universally beneficial. “Flexibility comes in many forms and may mean different things to different people, at different stages of life”. For Basma, flexibility proved crucial during significant life changes, allowing her to adapt and thrive in various circumstances. Basma’s leadership approach begins with placing trust rather than verification. “My starting point is always focusing on delivery excellence. I trust individuals to be best placed to know how they can manage their time whilst not impacting their productivity”. By empowering her team members to take ownership, Basma has repeatedly managed to build healthy, high-performing teams. “This approach has proven effective in creating a culture of mutual respect and accountability, where team members feel valued and motivated to achieve their best work.”

Despite progress, Basma recognises ongoing challenges. Referencing research on women’s advancement, she noted that “there has been effort over the past 10 years to promote women from entry roles to leadership positions. However, organisations seem to be in a state of limbo now where things aren’t progressing as quickly as they should”.

To maintain momentum, Basma advocates for calculated risk-taking. “Women should take more risks. Why do we shy away from that?” She spoke of the power of visibility in encouraging this. “Having gone through different stages in my life and career, I feel as a leader it’s my responsibility to share my stories with individuals at the workplace to normalise conversations, help them navigate challenges, play a championing role and hopefully inspire them. All of us go through similar sorts of challenges at different times in our lives. It’s important to recognise this and support each other by connecting at a human level”.

Basma also addressed the internal pressures many professionals face. “As high achievers, we want to do well and create impact. This can sometimes create unnecessary pressure and many a time tends to be self-inflicted”. Basma’s experience has taught her a different approach: “Over time, what I have found is just by pacing ourselves more and taking that kind of pressure off, has much longer-term returns”.

Through both her words and leadership example, Basma demonstrates that inclusive environments in STEM require both structural flexibility and a recalibration of personal expectations. Her insights and approach serve as a valuable reminder that achieving excellence is not just about pushing harder, but also about finding balance and supporting each other along the way.

Thank you, Basma, for your time and reflections.

Interview with Esther Elbro, Principal Project Manager, Research, Technology & Innovation

With an academic career spanning more than 30 years, Professor Jennie Stephens is Professor of Climate Justice at the ICARUS Climate Research Centre at the National University of Ireland Maynooth. Born in Ireland, Jennie has spent much of her life and career in the US, so her current position is somewhat of a homecoming. We sat down with Jennie to learn more about her work on gender and climate change, and her experiences of a changing workplace.

… Jennie initially started down a more technical scientific route. “But I became increasingly aware,” she reflected, “that a lot of scientists don’t speak up on policy and aren’t actually advocating for or getting involved in the transformative changes that are urgently needed. I realised I wanted to shift my focus and do work with a bigger, more direct influence on society and social justice. Different opportunities have emerged in the science–technology–policy space that links the climate crisis to worsening economic injustices.”

This broadening of focus and connecting of dots brought with it another epiphany. “I realised how the mainstream approach to climate change is very male dominated, technocratic, patriarchal, and kind of controlling – many so-called “climate solutions” are based on the idea that humans have control over nature, and that we can develop technologies to fix the climate. I started realising that this way of thinking would never be transformative enough – and it actually reinforces the status quo. So I am an advocate of alternative approaches that are based on human rights and social justice. We need diversity of thought and diversity of perspectives and skills in order to become more transformative in our thinking and in our policies. So that’s where the feminist lens came into my work – based on my own experiences, really.”

… however, with some established colleagues questioning the utility of this approach. The very same power dynamics and structural disadvantages at the heart of Jennie’s academic work were also at play in the environment in which she was operating. “There was a time when I was doing a lot of energy technology research, and I attended big conferences with probably 95% men in the room. A lot of panels at these conferences were also all men speaking and presenting.”

Nevertheless, some of the connections made with other women in the room proved particularly fruitful. Over lunch at one such conference, Jennie recalls that she and a small group of other women attending started discussing different research ideas, leading to collaborative research proposals with a more social and equity justice focused approach, which went on to receive funding. “That all emerged,” Jennie reflected “because we connected in a different way in a very male dominated space.”

Jennie is a big believer in the power of networking and puts a lot of the success of her early career down to making connections with other people in her field. “I’ve always been quite collaborative in my work. I meet a lot of people and learn different things from different people I meet. Early on, I realised the value and opportunities of collaborating with people with different backgrounds, disciplines and experiences.”

… Jennie has recently published a new book Climate Justice and the University: Shaping a Hopeful Future for All (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2024). The ideas in this book are based on her own experiences of working on climate justice and energy justice in higher education for over 30 years – mostly in the US. Her 2020 book: Diversifying Power: Why We Need Feminist, Antiracist Leadership in Climate and Energy made the case for the need for diversity in thinking about climate and energy policy. Now in her current role at Maynooth, Jennie is keen to remain at the cutting edge of her field – critiquing the status quo and imagining alternatives – and pointed to the Spring Meeting of the Climate Justice Universities Union, ‘Building Collective Power for Feminist Climate Justice in Higher Education’, held in March as a particular highlight. She is also excited about continuing to advance the idea that higher education institutions are more than just places where individuals go to get a degree for career purposes. They’re also “central to legitimising different policy discourses and should also be thought of as critical social infrastructure providing support and resources for all during this increasingly disruptive time.” Jennie sees real potency in this idea in the context of our rapidly changing world.

When asked what advice she would have for those starting their career in the climate justice and the environmental policy space, Jennie said that she would encourage people to follow their interests and what they are passionate about. “Don’t try to follow the path of others. It’s a really dynamic time. Things are changing quickly in the world. Different kinds of leadership, different kind of skills, different kinds of networks are going to be important. I think there’s more new opportunities and pathways than anyone assumes.” While for some a career might be linear, that’s not the case for many people “You have to be able to respond to the time and opportunities in front of you,” Jennie counsels.

Thank you, Jennie, for your time and reflections. We very much look forward to seeing where your important work continues to take you.

Nilanjana Pal is the Executive Director for CASE Asia-Pacific. She has over 20 years’ experience in research and advisory services across the higher education, corporate, and public sectors alongside a wealth of knowledge of the Asia-Pacific region and extensive experience in establishing new businesses and collaborations in Asia.

Nilanjana shared with us her reflections around the progress she has seen with regards to gender equity, and the work that still needs to be done. “Progress in education (my sector of work) has been heartening – more women than men are attaining tertiary education, girls are staying in primary and secondary schools longer… all of these achievements in closing the gap in education between genders have led to profound, multiplicative, positive changes in families and communities around the world. As the African proverb goes, ‘you educate a girl, you educate a nation’!”

Despite meaningful progress, there are many areas where action is needed, including “gender-based violence, equal pay for equal work, and inadequate attention to women’s health issues. Financial independence for women remains a distant goal in many societies.”

“I think the structural barriers remain the same, regardless of sector or geography. That also tells you something about how difficult it is to dismantle these unequal systems. Women bear the brunt of caregiving responsibilities, household chores, they take a hit on their careers due to childbearing…the list of systemic barriers is long!”

However, Nilanjana noted that “progress exists in surprising pockets. For example, did you know that India has the highest percentage of female pilots globally? About 12.4 percent of Indian pilots are female, relative to 5.5% in the US and 4.7% in the UK. Somewhat counterintuitive given prevailing gender and cultural stereotypes about professions, but true! Some of the reasons behind this surprising trend are progressive government policies that have prioritised recruiting women in to specific roles, supportive families, and inclusive and flexible workplace policies that have eased the entry and retention of women. Imagine what would be possible if we replicated this support system (and dismantled barriers) for women in other professional fields?”

In her sector, Nilanjana has seen first-hand how momentum has created tangible change. “Several of the top universities in the world now have female academics leading these institutions. This would have been inconceivable even two decades ago.”

In the current climate, it’s important to ensure that women’s rights remain a priority. In thinking about how we can ensure this, Nilanjana noted that “each of us have a responsibility to speak up if we observe an injustice, to reach out to those in vulnerable positions and to support one another. We also have to involve men in this pursuit for equality. Without partnering with men, no change is sustainable.”

… to ensure that women’s rights are represented in legislative procedures. We should all donate (time, money or both!) to organisations that support our values. Be generous. Stay focused. We cannot drive positive impact if we are not willing to put our finances and time towards the initiatives that matter the most to us.”

Throughout her career, Nilanjana has been working to drive impactful, long-term change. “I have been championing the education of women my entire adult life. This has taken various forms.” As an alumna of a women’s college, she has focused on “advocating for the education and empowerment of women from diverse backgrounds, and ensuring they have a path to the kind of transformational education that I was so privileged to receive, helping in the admissions process, donating time and resources to these institutions, and offering career advice and mentorship to young women who are just starting out on their professional journeys.”

… Nilanjana reflected on the importance of visibility. “Ensure that your colleagues and senior leadership represent the diversity of lived experiences and capabilities that exist in our societies. Implement transparent recruitment measures that help overcome institutional or individual biases. Seemingly small actions matter and go a long way to building an inclusive workplace: respecting traditions, foods, work practices that are different from the dominant culture at the organisation and demonstrating a genuine willingness to learn more about these differences.”

Speaking on the accountability piece, Nilanjana noted some of the initiatives in place at CASE to promote gender equality. “We affirm their seat at the table, offer flexible working practices and access to mentorship and professional development opportunities.”

We would like to thank Nilanjana for taking the time to share her thoughts with us and we look forward to seeing her continued, impactful contributions at CASE and beyond.

Interview with Kate Hunter, Partner, UK Higher Education

On the occasion of International Women’s Day, we sat down with Lysa John, Executive Director of the Atlantic Institute, to discuss the challenges and opportunities facing women’s rights in today’s complex global landscape. Lysa is a passionate advocate for human rights and gender equality.

… Lysa articulated – “The one thing organisations talk about least is their values. One of the best phases of my life was working for Yuva in Mumbai. We constantly discussed values and how they related to our view of the world and our work – it was fundamental to our language about projects and research.”

“Sadly today, the values debate has become so extreme that it’s difficult to ground yourself and talk about the values you’re showing up with. Does this work and workplace speak to my values? The good news is that many young people in activism are creating non-traditional spaces where this debate thrives.”

“It’s not just about values published on a website – it’s about having a constant dialogue about values in practice. These conversations get shut down when people feel it’s risky; there’s a lot of anger and emotion around issues like Gaza and Sudan. But we can’t work for equity if we can’t have difficult conversations – if we don’t have the language and tools to navigate those conversations.”

Looking at women’s rights from a macro perspective, Lysa pointed out that there is a tangible connection between democracy and women’s rights. “When we see backsliding in democracy, women and LGBTQ+ groups are invariably affected. Look at the culture wars in the US – attacks on abortion rights and other issues. Women’s rights are used to polarise communities and assert a masculine, militaristic form of government. Democracy involves participation and consultation, which is often seen as very feminine and goes against strongman politics and culture. An attack on one usually means an attack on the other.”

However, the political threat is not the only global challenge to women’s rights Lysa highlighted. “When we talk about women’s rights, it’s not one monolithic issue. There are so many strands around moral and cultural space, political participation, and women in work.”

“40% of women don’t have access to the internet – something we don’t think about much. Most women globally are employed in the informal space, which leaves them constantly vulnerable. One in ten women lives in extreme poverty, directly linked to gender. Women are the largest proportion of migrant workers and provide the highest and most regular levels of remittances.”

… the largest form of transfers for those in need comes through remittances, with women being the largest ‘donor’ group. Despite facing so many structural setbacks to their progress, they’re still committing and investing in communities and societies.”

However, there is still hope and despite the current challenges, there has been progress made – “There’s a lot of backlash and bad news around women’s rights. But it’s also true that it’s the most persistent movement around advancing rights in very tangible ways. Issues around reproductive rights become controversial and polarising, but they also generate an equal amount of energy to move rights forward, to fight back.

“The articulation of workers’ rights was non-existent before. It’s similar to the climate movement today – headlines focus on losses, but there’s tremendous work happening on the ground.

“The CIVICUS Monitor identifies bright spots every year – advances in women and gender justice, primarily through legislation and litigation. We’re fighting a culture war around societal norms; our biggest resource is codifying progressive norms. But you need behavioural change alongside laws, whether addressing gender-based violence, equal pay, or protection in various environments.”

Lysa’s words remind us that International Women’s Day is not merely a celebration, but a recommitment to the ongoing work of justice. Her insights offer a clear-eyed assessment of current challenges and the historical perspective that gives us the courage to continue.

Interview with Shivani Smith, Partner & Sector Lead, Social Impact & Environment (UKAME) and Arshya Dayal, Senior Research Associate (UKAME)

Charla Griffy-Brown is an accomplished leader in the arenas of digital innovation, analytics, and technology development. She is currently the Director General, Dean, and Professor of Global Digital Transformation at the Thunderbird School of Global Management, Arizona State University (ASU), a position through which she continues to lead transformational change. We sat down with Charla to discuss her career, the progress she has seen on equality so far, and what she hopes to see in the future.

Charla opened up about her formative years and the seminal role her family played in shaping her outlook on the importance of shared humanity. After graduating from Harvard, she embarked on a Fulbright Fellowship in Japan and moved to Australia to complete her doctoral degree. “The Australian perspective of equity and access to education which they see is very much a human right. It’s not just a civil right.” Having later worked in India, China, and Indonesia, “I gained a lot of perspective on how women were disadvantaged in different cultural contexts as leaders.”

Now at Thunderbird, Charla is proud to be part of a team creating opportunity for others. “We’re always asking the question ‘who’s missing at our table’ because we understand that the leadership of the future has to constantly be considering different optics if we are going to advance in ways that will benefit all of our communities and ultimately create sustainable shared prosperity.”

Discussing the meaningful progress she has seen, visibility and mentorship were key themes. Charla is proud of ASU having embedded this into their leadership structure. “One of the most significant and inspiring leaders is our Provost here at Arizona State University, Nancy Gonzalez.”

“I’m so excited to see more women entrepreneurs and female-led startups, and I think many countries and organisations are really recognising the power of investing in women’s businesses, and helping to get them access to capital and global markets and ultimately how this leads us to more thriving communities.” Charla also noted how remote work had become an equaliser for women’s work, as had the digital space, allowing for more flexibility and access to leadership but also to fight changes in policy and drive inclusive innovation. “There is a big generational and cultural shift – there is a societal recognition of the value of inclusive leadership.”

Though there is plenty to be proud of, Charla noted there are still some barriers. “Breaking the glass, or in some cases the concrete ceiling, is in progress. But we are still underrepresented, particularly in executive roles in STEM and finance. There are systemic biases and I think they persist in hiring, promotions, and decision making structures. There’s still a lot of work to be done in access to capital and financial inclusion. Women led businesses still receive a disproportionately smaller share of venture capital funding and financial systems.”

…Charla was particularly excited to share some of the existing resources at Thunderbird. “The biggest piece of advice would be to access resources that are available to help you.” Specifically, the Najafi 100 Million Learners Global Initiative, which supports women entrepreneurs globally. “We’re seeing significant change in communities because of the ability to access and be empowered through knowledge. Our goal is to provide the highest quality education and make that accessible to everyone.”

“We need to lean into the progress that has been made already. The fact that we have women in the boardroom is going to change the dynamics of how those decisions are made and open up greater opportunities. I think we need to vote, exercise whatever tangible empowerment we have, and we need to continue to have these types of conversations where we elevate and make visible not only what is happening, but why it’s important and how it’s important to our communities, to our families, to the future, that we want to create together. That’s what we need to keep in front of us.”

“We are at a pivotal moment where global digital transformation, entrepreneurship, and policy innovation are creating new avenues for women’s leadership. But real progress demands intentional efforts in mentorship, investment, and systems change. The work is far from over, but the momentum is undeniable. Let’s double down on impact—supporting women not just in leadership, but in shaping the future of business, governance, and global problem-solving.”

Thank you to Charla for sharing her time and insights with us. We are excited to continue to watch her journey at Thunderbird.

Interview with Isabela Betoret Garcia, Senior Research Associate (UKAME) & Sarah Snelling, Project Manager (UKAME)